Android Wear doesn’t seem to have set consumers’ hearts racing. Photo by pestoverde on Flickr.

In my estimate last week of the number of Android Wear downloads, and hence actual “sell-through” (as it’s called), I used the number of reviews left on the Android Wear app page and drew a straight-line extrapolation from that, and from various known waypoints, to get my estimate for the number in use – which was about 1.9m, up from 0.7m in February 2015.

Among the provisos, though, was this one:

My previous estimate worked on the basis that the number of comments was proportional to the number of downloads. I don’t see any reason to change that assumption.

Oh, behave

Having said that, I’ve thought a bit more about likely consumer behaviour, as well as what the data actually shows us.

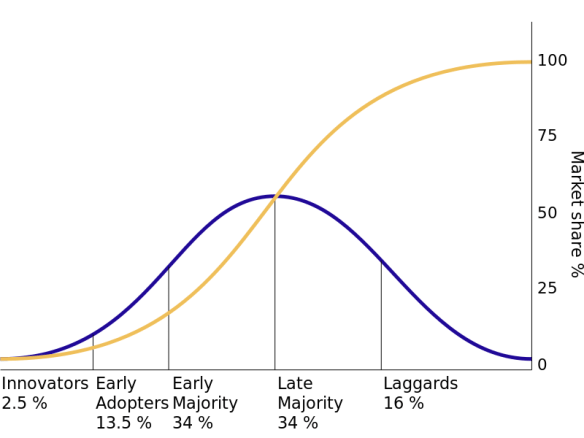

We know that as more people get to use something, the number who actually comment on/review it falls – it’s just human nature that early adopters are the most likely to be vociferous, whereas those who follow are less troubled about it. After all, who wants to be the 1,900th commenter below an article?

So I took a look at the number of comments* per download, for the waypoints where we know the number of downloads for sure. We know those waypoints because the Google Play figure abruptly goes from saying, for example, “number of downloads: between 10,000 and 50,000” to “between 50,000 and 100,000”. Obviously the 50,000 download point has been crossed between those two points. (* “comments” not “reviews” because they’re not necessarily reviews; you can make them without having downloaded the app.)

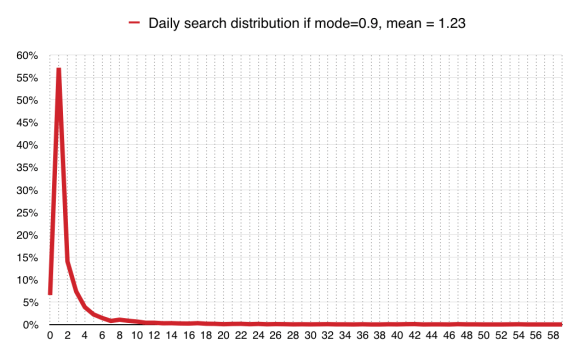

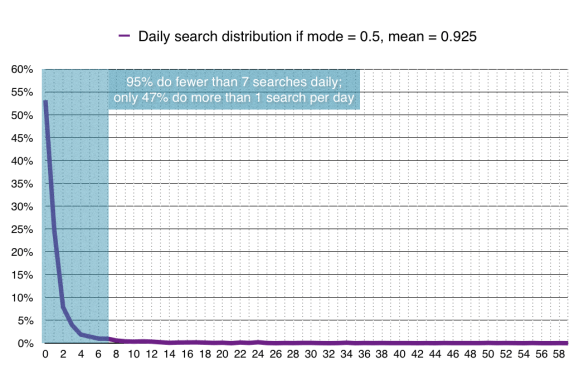

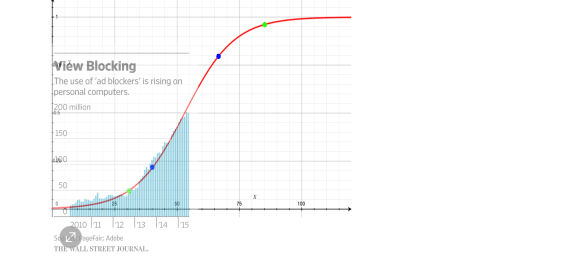

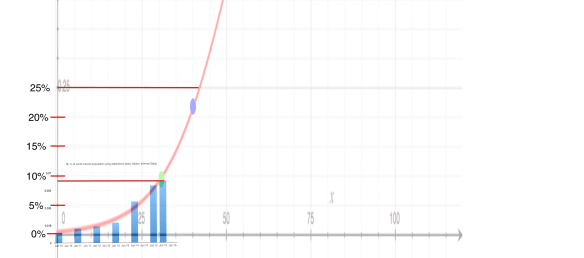

So I marked those points, and the number of comments at those points, and tried to find the best fit curve. I get this:

The data seem to suggest that the number of downloads required to generate a new comment grows over time; currently we’re at the black mark.

(That’s an R-squared of 0.89, using a logarithmic fit; it’s the best value of R-squared I could get out of trying a linear, logarithmic, polynomial, power and exponential fit.)

What this is telling us is that to begin with, you get lots of reviews/comments for every download. Right at the start, there was a comment for more than one in every seven downloads. By 100,000 downloads there are 4,032 comments, which means by then, on average, every 24.8 downloads someone had left a comment.

But by the time you get to 500,000 downloads, there are 14,981 comments – so on average it has taken 33 downloads to get each comment. By the time you get to a million downloads, the average has fallen to 44 downloads per comment.

A certain ratio

This is the sort of behaviour we’d expect: early on, lots of people are mad keen to give feedback on their experience; and then it tails off, until we’re dealing with a gradually falling ratio as the numbers of downloads head into the multiple millions.

Fitting this to that curve (which is the only data we’ve got, absent sales figures or numbers from Google) tells us that we’re currently at about 57.5 downloads per comment overall – that is, over the whole time Android Wear has been going, on average you get a comment every 57.5 downloads.

And how many comments are there? Currently, 47,620 (with the average review score just dipping under 4.0). How many downloads is that, and hence how many sell-throughs? Pretty simple:

47,620 comments * 57.5 downloads per comment = 2.74m Android Wear downloads.

This is quite a bit bigger – 44% more – than my previous estimate of 1.9m Android Wear users. There are (as always) potentially confounding factors, which would tend to reduce the actual number:

1) some people may have left more than one comment/review.

2) you can leave a comment/review without having actually downloaded the app

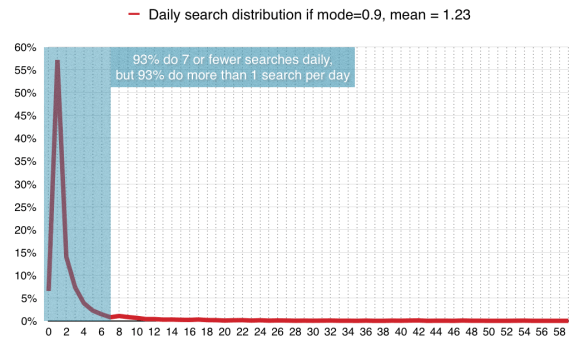

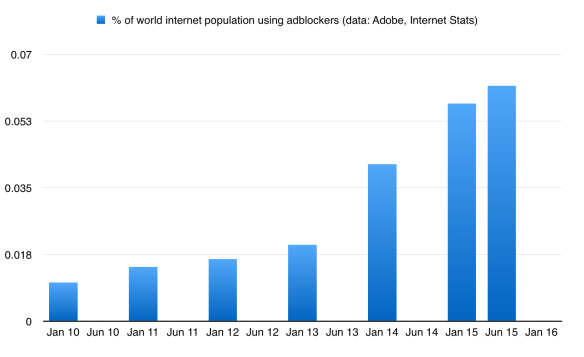

3) the number of comments added per week is quite variable – as below:

Sometimes you get a lot of comments on Android Wear – and sometimes you don’t. Does that match downloads? Hard to say.

This is possibly prompted by the release of new versions: a number of people commented on 9/10 November about the new version and its removal of battery stats. That’s going to bump up the apparent number of “downloads” while the actual number in use is no different.

On the whole, I feel comfortable suggesting that the correct number probably lies somewhere between these two – the straight-line extrapolation and the “reducing comment” number. In other words, somewhere between 1.9m and 2.74m. (The midpoint is 2.32m.)

Quite probably the only way to be sure will be to watch the Android Wear page and spot when it crosses the 5m download mark. Is it going to be before the end of this year, though?

Only maybe, at least if we go by IDC’s forecast for how many Android Wear devices will be shipped this year. In a press release in September, IDC reckoned that there would be 4.1m shipments of Android Wear devices in 2015. That would take the total activations by the end of 2015 to 4.7m, as at the start of the year it was around 0.6m (it passed 1m activated in late February, by my data). As long, that is, as those shipments are actually bought by people, rather than sitting on shelves.

Comparing that to my estimates for the number activated so far this year – a low of 1.3m (1.9m – 0.6m), and high of 2.1m (2.74 – 0.6m) – we’re left with somewhere between 2.8m (4.7m – 1.9m) and 1.96m (4.7m – 2.74m) to be shipped, sold and activated in the next couple of months around Christmas if IDC’s target is to be met (and if my estimates are correct). So, the week following Boxing Day could be fun.

Low, high, in between

There are some other numbers: Strategy Analytics says that in the second quarter, Android Wear shipments were just 0.6m units; for the third quarter, it says that Samsung shipped 0.6m and “Others” (including Pebble) 1.0m. We don’t know how many of the Samsung ones were running Tizen, and how many Android Wear; nor how many Pebbles were shipped. If we ignore that, we get 1.6m Android Wear shipped in the third quarter; 2.2m since March (when the 1m download point was passed). If they’re all in use, there might be 3.2m running.

Even with the high estimate, it begins to look like maybe this is going to be one of those spaces where Apple shows how the category should look, and grabs the majority of sales and profit – as it did with the iPod and iPad. Because Strategy Analytics reckons that in the third quarter alone, Apple shipped 4.5m units – more than Android Wear has all year.