|

This is the first of a series of posts illustrating points from my book Cyber Wars, published May 3 2018 in the UK (and a couple of weeks later in the US), which investigates hacking incidents such as the Sony Pictures hack, the TalkTalk hack, ransomware, the Mirai IoT botnet. It looks at how the people in those organisations responded to the hacks – and takes a look at what future hacks might look like. |

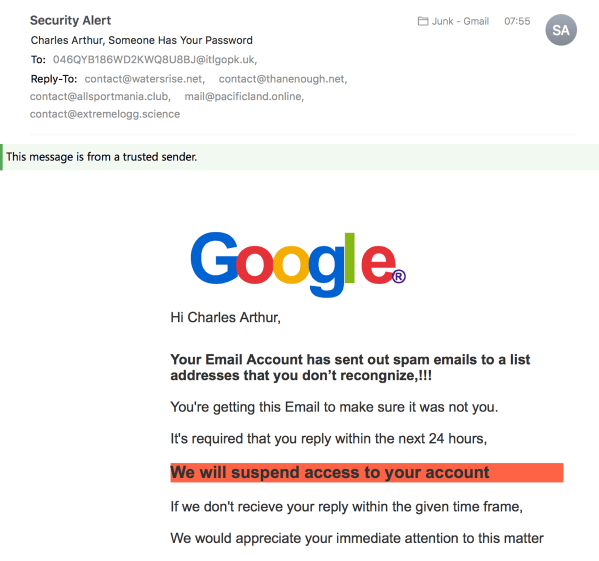

Another Monday morning, and an email drops into my inbox.

Well. That looks serious, doesn’t it? They’ve got my name correct. But you can see (especially on this version, the desktop one) that lots of things are wrong about this email.

Let’s enumerate them:

• the To: address is incorrect (clearly it reached me via a Bcc: address)

• the Google logo is all wrong: the characters are bunched up, rather than evenly spaced. (When I looked at the source code of the email, it turns out this was done in CSS, rather than an image. Designers will commiserate at the kerning failure.)

• the first sentence doesn’t make sense and isn’t grammatical and contains misspellings

• Second sentence capitalises “Email”, which isn’t standard spelling

• Third sentence ends with a comma rather than a full stop

• Fourth sentence (in red) doesn’t quite show what you need to do

• Fifth sentence spells “receive” wrongly, and ends with a comma

• Sixth sentence is stilted and lacks a full stop.

Not hate mail, fake mail

Overall, there are all sorts of indications that this is a fake email. It’s phishing: the obvious aim is to get people to reply to it, after which – one can predict – the phishers will respond by sending an email with a link to a page telling the victim to log in. It will be a fake Gmail login page, and once that’s done, they’ll be able to get control of the victim’s email (and lock them out by changing the password), and from there probably any account, possibly including their bank and other utilities. Any account whose password recovery, or password system, passes through that Gmail is going to be compromised.

You might look at that email and laugh, thinking it’s obvious that it’s a phishing attempt – you’d never fall for that. But phishing is a very old technique (want to know how old? It’s in the book, but if “AOL” rings a bell, that’s a clue), and has been refined over the years.

Just as with the “419” scam promising you a huge fortune if you’ll only send over a bit of money, phishing’s practitioners have learnt that a few intentional mistakes can actually increase the chance of success – because the people who don’t spot spelling mistakes or oddities about the From: in an email probably won’t know what phishing is either. (In 419 scamming, they intentionally write in a stilted, naive fashion because the recipient then thinks they are dealing with fools who can be stiffed. The truth is exactly the opposite.)

Sophistication nation

A rather more sophisticated version of that phishing technique is exactly how the inbox of John Podesta, Hillary Clinton’s campaign chairman, was hacked in the 2016 US Presidential election. (The story of that makes up chapter 4 of the book.)

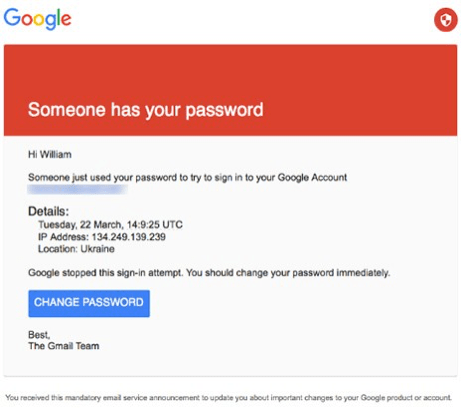

The campaign team monitoring Podesta’s emails weren’t going to be fooled by something like the message above.

But they could be caught by the one that Russian hackers sent, which looked exactly like a standard Google phishing warning.

Now that is a lot more sophisticated. And Google does send out “suspicious login attempt” emails.

This phish purported to be from Gmail to Podesta’s inbox, saying that “Someone has your password”. (There was actually a subtle detail – it’s in the book! – that got that past Google’s filters.)

That” CHANGE PASSWORD” link led to a fake login page, where Podesta’s details were entered, and… calamity followed. (And contrary to some expectations, it wasn’t Podesta who entered those details.)

One point worth noting is that this was Podesta’s personal inbox. His campaign inbox? The inboxes of other staff? Those weren’t hacked, because they already had crucial protection: two-factor authentication. The fact that it was Podesta’s personal, not campaign, email that was hacked disappeared in the melée, but it’s a relevant point. The campaign also used another communications method to defeat would-be hackers; that’s in the book, and I’ll deal with it in a later post.

The lesson

Turning on two-factor authentication (2FA) is the single simplest method you can take to improve your email, and general computer, security. Google doesn’t push it hard enough, in my view. A survey of 2,000 adults in multiple countries in May 2016 showed that 70% don’t have 2FA turned on. Yet it’s easy, free, and increases your security enormously; it also reduces the need to worry about getting phished. (You can still get phished if you use 2FA, but it needs more sophisticated work on the part of the phisher.)

This page shows how to turn on 2FA for Gmail. (I’d recommend using an on-device app rather than SMS for codes; SMS can be hacked.) If you use a different service, try a search on 2FA with its name.

In short, 2FA means that you either generate a device-specific password for every device you use, or that you have to authenticate each time you log in your email on the device using your email, password and a “TOTP” – timed one-time password. (It’s a six-digit code generated from a 40-digit number which is in turn generated from a combination of the time when you login, and a “seed” number stored on both the server and your device. If the number generated by the server and by your device agree, then you’re authenticated.)

If you don’t have 2FA turned on, then there is always a risk that you’re going to get phished. You spotted the one above. Will you spot every single one? Remember, they only have to fool you once; you have to defeat them every time. And there are lots more of them than you.

Thanks for reading. And even if you don’t buy the book, please turn on two-factor authentication. Everyone, including you, will be so much happier.

|

This is the first of a series of posts illustrating points from my book Cyber Wars, published May 3 2018 in the UK (and a couple of weeks later in the US), which investigates hacking incidents such as the Sony Pictures hack, the TalkTalk hack, ransomware, the Mirai IoT botnet. It looks at how the people in those organisations responded to the hacks – and takes a look at what future hacks might look like. |

I also do a weekday roundup of interesting links called Start Up, posted here each day at 0700 UK time; or you can receive it as an email (roughly an hour later). Sign up here. You’ll get a confirmation link before you start receiving anything.

Unsubscribing is as easy as clicking a link, which will put you through to our customer service representative who values your call so much they’ll make you wait 10 minutes listening to 20-second clips of music interrupted with pleas not to go away and then struggle to hear you over the cheap VOIP line provided by a cheapskate outsourcing company which also hasn’t given them any power to actually act on your account.

No, wait, that’s the other people. With my one, you just click the link.

I’m looking forward to reading the book.

It’s the messages in non-email environments that worry me, where we’ve not yet been taught to question them. The SMS that says you’ve requested your WhatsApp account is moved to a different phone, please call this (very premium rate) number. The ‘free wifi’ in Doha airport that invites the user to login using their Apple ID and password. The latter was a clever piece of phishing given how Google and Facebook allow their accounts to be used in this way.

The behaviour change challenge to use 2FA among less savvy users is immense.

Excellent points, Joel – I think I’ll try to deal with those in a future post.